New Museum Aims to Tell ‘Lost’ Stories of Grand Rapids’ African-American Community

Julie Bitely

| 3 min read

It’s the story of four families who fought back against redlining to build their dream homes in what is now Grand Rapids’ Auburn Hills neighborhood.

It’s the jazz singer who performed in Division Avenue clubs before African Americans were allowed to do so.

“She sang so well, they just let her sing,” said George Bayard III, executive director of the recently opened Grand Rapids African American Museum and Archives (GRAAMA).

George Bayard III in front of the newly opened Grand Rapids African American Museum and Archives at 87 Monroe Center St. NW in downtown Grand Rapids.

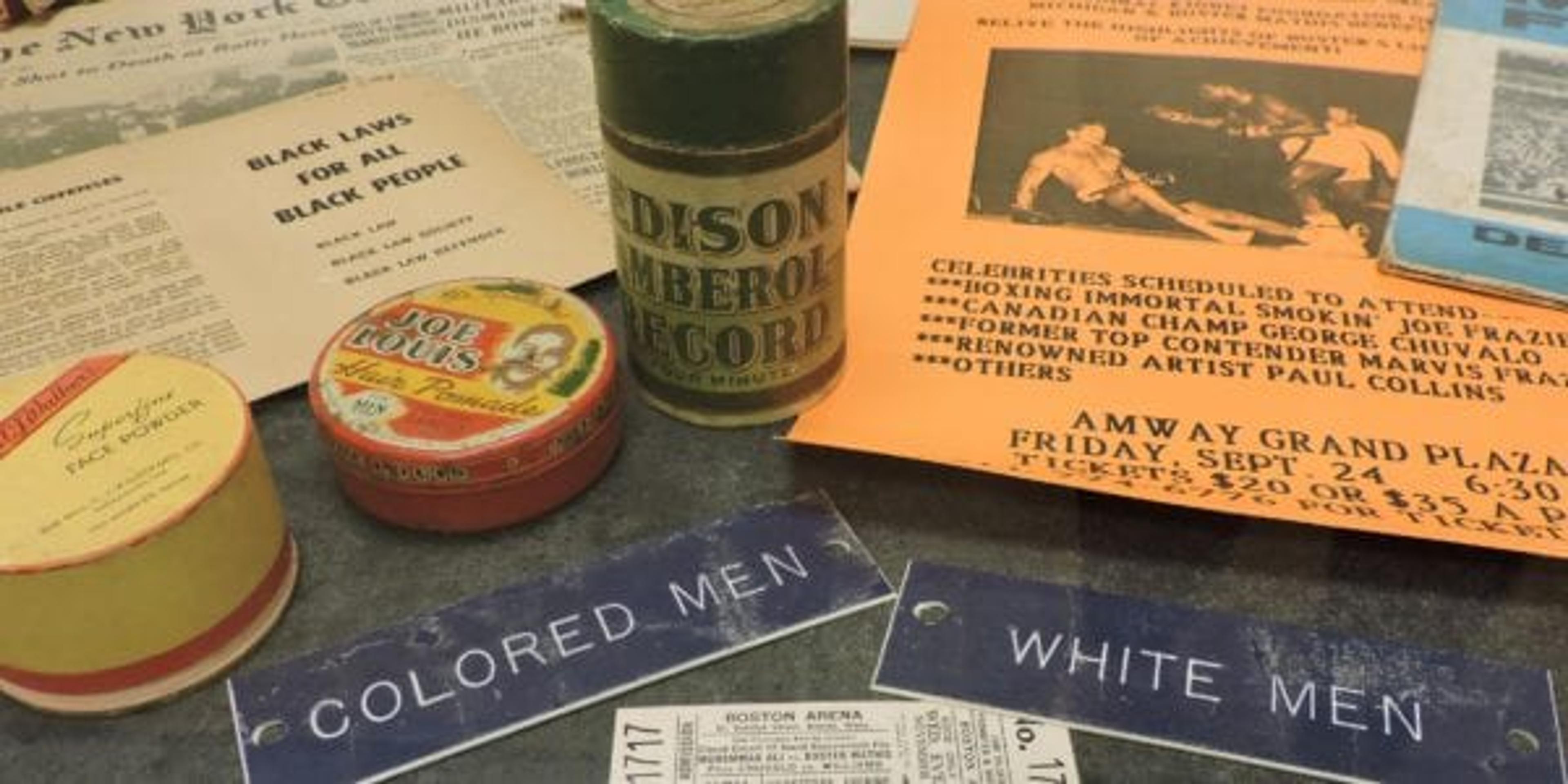

It’s union organizers, baseball players, civil rights activists and everyday people too. Bayard said the museum will tell the stories of Grand Rapids’ African Americans, weaving together a comprehensive picture of local lives, culture and history.

“One of the reasons we did this is that the stories of African Americans here in town were just getting lost,” Bayard said.

While smaller Michigan cities such as Big Rapids and Muskegon Heights have dedicated African-American history museums, as well as one of the largest in the country in Detroit, Bayard said it was about time for the state’s second largest city to remember and celebrate its rich past.

“What we want to do is tell the story all year long because we believe the stories are that important to tell,” he said.

Bayard has been hard at work organizing and displaying his collection of artwork and historical artifacts at the museum’s temporary location at 87 Monroe Center St. NW. The cultural institution quietly opened its doors during ArtPrize and plans to stay in the heart of downtown for at least two years while fundraising takes place for a 10,000- to 13,000-square foot space, which would take up permanent residence on the city’s southeast side or downtown.

Eventual plans include dedicated space for permanent and touring exhibits as well as a performance and meeting center space for concerts, movies, lectures and receptions. A place to store the many archives, records, tapes and memorabilia that Bayard has collected since moving to Grand Rapids in 1988 would also be possible in a larger space. Bayard believes more historical material likely exists in the basements, attics and trunks of many Grand Rapids residents and he doesn’t want to see them discarded.

“We don’t want them to be thrown out,” he said.

Through a grant from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation via the Michigan Humanities Council, museum volunteers have embarked on an oral history project, recording interviews with local seniors who lived through segregation and Jim Crow laws, the civil rights movement and so much more.

Bayard ultimately hopes the museum and its displays will showcase the hardworking and influential people that have made the Grand Rapids African-American community strong and vibrant, inspiring young people to dream big and reach for more.

“There’s enough that we can show in the museum that will inspire young people to a higher plane,” he said.

You can help support the museum’s fundraising efforts at their Facebook page or check their website for current hours and to plan a visit. Contact museum staff if you have any relevant historical artifacts or documents you’re interested in donating.

If you enjoyed this post, you might also like:

Photo credit: Julie Bitely